The Gates of Creation is another unusual and outré adventure in Philip José Farmer’s World of Tiers series, though, like most sequels, it isn’t as fresh as the first. It has plenty of action and adventure to keep you in your seat, and its brevity (under 200 pages) works in its favor to boot. Farmer has an admirable facility for not wasting time, or padding out his tale with needless exposition.

Whereas The Maker of Universes called upon a broad spectrum of religious tradition for its combination of allegory and satire, Gates has been fashioned specifically as a pastiche of the religious poetry of William Blake, particularly such works as Vala, or the Four Zoas and The Book of Urizen. Farmer explicitly derives many of his characters’ names and personas from these poems, as well as the underlying theme: the loneliness of immortality and the vengefulness of gods.

Opening an unspecified amount of time after the events of Universes, the story pits Robert Wolff — who has now reclaimed his position as the Lord of the World of Tiers, though he has renounced his former tyrannical ways — against the treacherous wiles of his father and siblings. Wolff’s father, Urizen, is the Lord of Lords responsible for initiating the creation of all of the “pocket universes” over which he and his children rule. (Farmer is still remaining deliberately hazy on where these Lords really come from, or how they create these universes, speaking vaguely about indescribably advanced technologies. Too much explanation would probably spoil the stories’ ability to function allegorically.) The thing is, the Lords have a tendency to tire of their creations — a problem you rarely see addressed in mainstream religion. What value would an all-powerful and omniscient God place upon existence if there was nothing left to know?

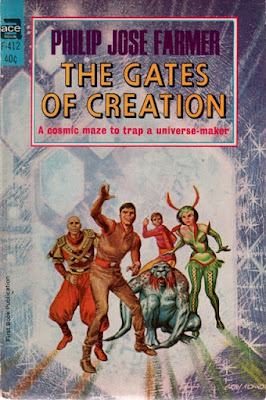

Wolff is confronted by Urizen one night and told that Urizen has kidnapped Wolff’s beloved Chryseis, and that to recover her Wolff must endure a dangerous series of trials. Traveling through a gate into his father’s universe, Wolff finds himself on an oceanic world where he encounters his numerous brothers and sisters — each of whom is suspicious and hostile towards all the others. One of Wolff’s brothers, the tragic Theotormon, has been cruelly transformed into a hideous fishlike humanoid. One sister, Vala, definitely has more going on behind her seductive smiles than she’s letting on.

Wolff, by the hardest, convinces this haughty consortium of mutual enemies to unite in the interests of finding and overthrowing Urizen. Thus they travel from world to world through a series of gates, never knowing where they’ll end up. And each world presents its own series of challenges that must be overcome before moving on to the next one, like advancing levels in a video game.

Farmer keeps the adventure ticking along generally well. The opening scenes on the waterworld, which include a spectacular pitched battle on an airborne, floating island, are the best. But it’s true that, even as short as the book is, the repetitive structure of the plot (journey to new world, barely escape death, struggle to find way to next gate, repeat) causes the whole thing to lose much of its steam along the way. And the absense of such colorful characters as Kickaha is a demerit. There’s pretty much nobody in The Gates of Creation besides Wolff to root for.

And yet the book rebounds handily in the seventh inning stretch, and delivers a satisfying, bravura climax. On another positive note, the numerous bizarre artificial worlds Wolff and his ragtag band of brothers and sisters are forced to traverse do a great job of demonstrating why Farmer was considered one of SF’s most fecund imaginations. Overall, The Gates of Creation is fun old-fashioned Saturday matineé entertainment that will make readers happy they are mere mortals after all. (SFF180)